Focus

Maybe our problems with focus in today’s world are arising because we think of focus as something that gets us more, when really what we should get from it, is less.

“I want to be more focused”

“Ok, why?”

“Because I’m so distracted all the time and I can’t get anything done.”

How many thousands of times have we heard the essence of this conversation, or entertained this thought form in our own minds?

Lately, I think focus has become more or less equated with productivity. It’s implicitly considered as a means to an ends. “I need to get focused so that ___” or “he could be successful if he could just stay focused”. It’s a thing that we all want in one form or another, and whether by $5 cups of caffeine, $200 noise canceling headphones, or $8000 retreats to Bali, we try to acquire it.

But strapping the idea of focus to productivity implies that if we aren’t being productive, we aren’t focused. What about recreation? What about rest? Some “productivity nuts” — you know the type (they hang out with the biohackers and passive-income-retire-by-40 people) have even made rest somehow a part of their productivity routines. They’re the ones buying digital rings that give them a score for how good or badly they slept.

I may be weird for this, but the last thing I want after a night of crappy sleep is my phone telling me just how bad it was. That seems like the perfect way to set the expectation of having a crappy day as a result 🤔. I’m sure they are useful as sources of information in some sense, but I think we have enough things scoring, quantifying, and scrutinizing our every waking moment…so leave sleep alone, dammit!

Here’s a theory to write your thesis on—

We can’t stay focused because we don’t actually want to be productive.

There, I said it. And I think it’s more than just procrastination or laziness. The level of material wealth we’ve achieved at this point in human history is absurd (as compared to the rest of known history, relative to the cultural west). In order to go get food I sit in a metal box with wheels that harnesses the power of exploding fossils by my moving my right foot a little forward and back. To make the money to buy the food, I stare at a screen, think, and move my fingers a bit.

Maybe it’s time for humanity to start working on other things. Going to Mars at lightspeed and curing cancer are probably still going to happen if we let our kids take art classes and maybe walk around in the woods time from time.

We now live in an era that 1 in 10 kids is diagnosed with ADHD. The blame is usually pinned on some combination of overstimulation from technology, processed food, traditional schooling, over diagnosis, or just bad parenting. The “solutions” to this “problem” — install an app to monitor screen time, buy juice cleanses, go to boutique kindergartens that cost 10k a month, take Adderall/Ritalin (if you can get any after those after the college kids use up the supplies every semester—sacrificial nuggets of focus devoured before the god of productivity if ever there was! [cramming, more like]), and ye olde ‘parental discipline’.

All of these are remarkably similar in one, very important aspect—

They are all additives.

Swallow the spider to catch the fly.

If you aren’t familiar with that nursery rhyme, click that link above ^ because I’m going to reference it a lot to illustrate this idea and you will be super confused why I keep talking about animals if not 😆

Firstly, in some cases, the inability to focus can certainly arise from biochemical imbalances in the brain, which can be more or less difficult to address with substances of any kind (natural or synthetic). If you’re reading this after taking your morning prescribed methylphenidate ****or ****amphetamine, please don’t take this as criticism or as a poorly informed call from a dim-witted and medically untrained fitness instructor to stop doing whatever you’re doing.

Quite the opposite.

The other day I was digging up a jade plant in my yard and I wedged my $20 Home Depot shovel under a particularly strong root and then jumped on the spade. Guess what? It broke. Jade plant is still there. Some jobs simply require more powerful tools.

But the key thing to remember is that there is still something to remove, regardless of how long it takes or what tools are required.

There is ultimately still a job to be completed.

If you’re already swallowing the dog to catch the cat, you’re still going to be fine, but just recognize that it might take a bit longer to find the fly (and please, don’t get to the point of swallowing the horse 😅).

Nobody who is selling you additive solutions will tell you that there is a point at which you no longer need the tools. Weeds are inevitable, so keep those tools in your shed, but we truly need not choose between perpetual toil and having our garden choked & overtaken.

So what is the job, then? What exactly are we trying to do? And why did we swallow the fly in the first place?

The thing that we truly lack is understanding of what “done” is actually like.

We clarify our true desire right there in the second statement from above—

I’m so distracted and I can’t get anything done.

What we want is for things to be done. Complete. We want the feeling after the to-do list is all checked off. We crave the freedom on the other side of those effort based experiences. We want space.

But we tend to immediately fill that space the moment it’s created.

I finished my work, so now I’m turning on the TV. I finished that book, so now I’ll start another. It’s good to work. It’s good to relax. It’s good to read. But what is the nature of that which experiences all of those things? Can we just be…that?

If, like me, you have a little logic & skeptic in your head, you might say, “we are already that all the time” and you’d be correct. I think that’s a super important recognition.

But how often do we actually experience ourselves as ‘that’?

If we are constantly filling the space in our be-ing with sensory experiences, we don’t experience the ‘that’ very often. Maybe never. Stuck in this cycle of filling emptying and refilling, over time, we begin to (mis)identify with the contents of our consciousness. You can be utterly and purely “focused” all the time, but if your attention is always being given to something, what else could be perceived other than the perpetual flood of composite experiences, one after the other?

That’s why we end up craving entertainment. Next time you realize you brought your phone into the bathroom, try staring at the wall instead, and you’ll feel that craving. And if that’s all there is, then the ultimate freedom we can experience would be having the maximum level possible of control over what comes into that space. So we have people dedicating their lives to surrounding themselves in their preferences, so much so that we end up identifying with those things.

You can hear this issue reflected frequently in every day language.

“Hey what kind of ice cream do you want?”

“I’m a chocolate person”

I think (to myself): “Really? You’re a person made of chocolate?”

What they mean to say is: “I prefer experiencing the taste of chocolate over other experiences.”

That’s obviously too damn long to say to your friend when they just want to know what type of ice cream to buy at the store. They’d probably start hating you if you phrased everything like that. Or maybe they’d love you for helping them become more enlightened 🤷?

Either way I think there’s a useful distinction to be made there—

Are you the sum total of your experiences, tendencies, and preferences?

Or, are you the space in which those experiences are happening?

Debates about where consciousness actually comes from aside, the point here is that it’s definitely possible to experience yourself as the condition of awareness in which all experiences occur. To step out of the stream of entertainment and sensory stimulation, and be able to observe it like a river flowing on by.

Most call that practice meditation, and it supports the previous statement very reliably because it’s an empirical truth (based on observation & experience, rather than theory & belief).

The key thing to understand is that it’s a state that’s achieved through subtraction, rather than addition.

Whether it’s a symptom of our society having sprung up recently from the Industrial Revolution and being still based on the idea that more is always better (to drive consumption), the fact we are mammals and need to constantly seek (more) food to survive, or just the sheer paradoxical feeling around the idea that “less is more”….the attitude of adding or buying or hacking our way to peace, presence, and contentedness is one to truly grapple with in ourselves on a daily basis.

It’s a classic monkey trap.

No surprise that we struggle with it, really, since we are descended from apes, right?

We are driven instinctually to grab hold of what little we can and hold tight. Yet we have grown enough consciously to perceive that the world is much larger than ourselves, and we are capable of gazing up into the night sky with wonder. We can see that the universe is “out there”, but we can’t let go of that darn apple and just be a part of it.

Our memories, ideas, preconceptions and images of ourselves become so precious to us that we’ll choose them over freedom repeatedly during our lives. It’s understandable if you’ve been misidentified with your thoughts for a while. If that’s all you’ve ever experienced, it’s all you know, and letting go of that requires direct and willing confrontation with the complete unknown.

What is a poor simple monkey to do then?

How do we learn to let go of the apple? What does focus have to do with it?

Luckily, we have this tool called yoga, developed thousands of years ago by humans on the other side of the globe to intentionally prepare the body and mind for states of deeper union & integration with the present moment, and all that arises there.

Dharana

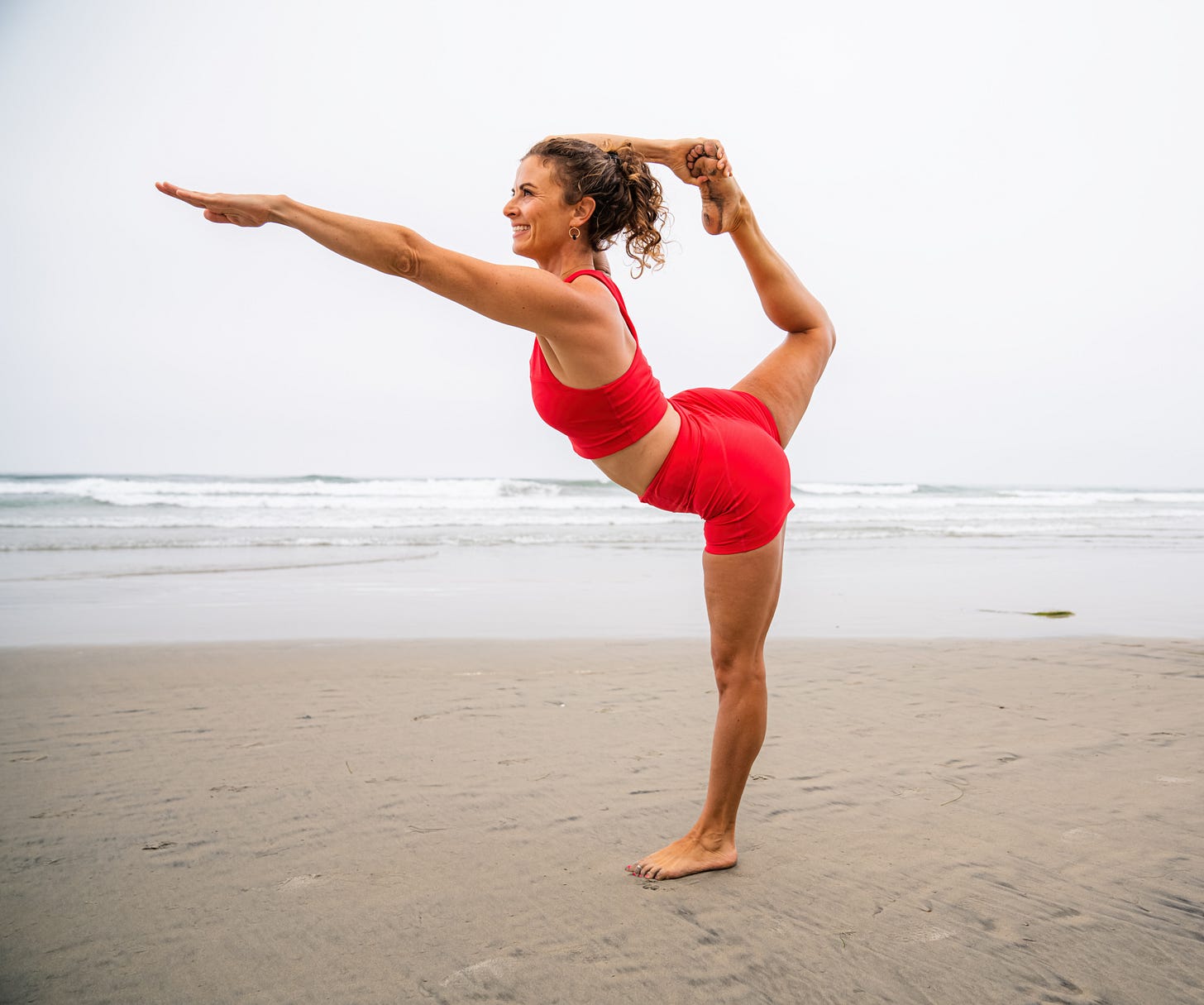

The 6th limb of yoga is Dharana, which translates to "concentration" or "single-pointed focus," and it involves training the mind to focus on a single object, thought, or point.

The breath is typically the most accessible object for practitioners. By calling the attention to the breath and attempting to hold it there, you create the opportunity of NOTICING when it’s pulled away by a thought or feeling. And that is truly a valuable experience because it can eventually lead us to the very simple realization: “I am not my thoughts”

Which of course leads to the question: “If not my thoughts (and the contents of my consciousness) then what am I?”

During a flow, we are cultivating Dharana every time we bring the attention back to the breath, or again, when we NOTICE that a body part is out of alignment, or feels a certain way. That’s why the 6th limb is preceded by the 5th — Pratyahara, the withdrawal of the senses. Closing the eyes, detaching from sound, smell, taste. Fasting from sensory experience. Pulling your attention back from the exterior world allows us to train focus on the inner experiences that can be veiled from view, escaping examination (and therefore understanding) when the senses are still distracted by all the various things that call them, filling the mind with information constantly.

However, the jump from the 6th limb to the 7th (Dhyana — Meditation) is anything but simple.

Well, it is actually pretty simple, it just tends to be super hard for members of our culture since we are trained to expect something more to come to us as the result of our efforts maintaining focus (it’s the additive attitude discussed above).

Traditionally, the 6th - 8th limbs of yoga are considered a crescendo. Dharana >> Dhyana >> Samadhi.

We develop single pointed focus (Dharana) first by training the attention on some ‘thing’ or aspect of the experience (breath, movement, thoughts, mantras), then we attempt to release the focal point but maintain the focus, so that what remains is just the awareness (Dhyana). In that state of center-less awareness, it’s possible to recognize that the illusion of separateness between you and the rest of the world has fallen away. That’s the point typically described as bliss, nirvana, pure presence, or being one with the divine (Samadhi).

The thing is, we don’t have much context for that practice of “releasing the focal point”.

This is where I feel that asana (what we mainly practice in the room) prepares us very nicely for meditation. We might not really notice it happening, but here’s how I’ve learned to see it—

Iyengar said in Light on Life:

Yoga teaches us how to infuse our movement with intelligence, transforming it into action. In fact, action that is introduced in an asana should excite the intelligence. When we initiate an action in asana and somewhere else in the body moves without our permission, the intelligence questions this and asks, “Is that right or wrong? If wrong, what can I do to change it?”

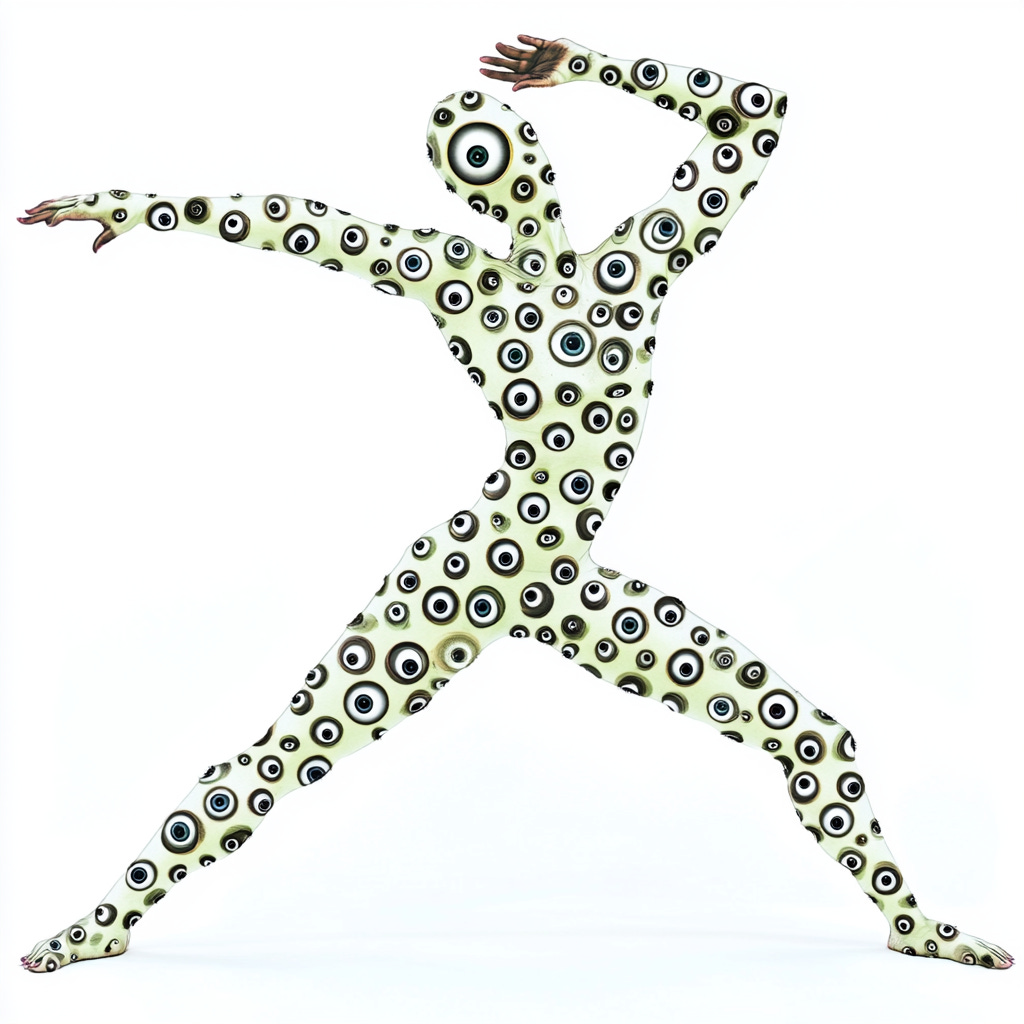

How do we develop this intelligence in the body? How do we learn to turn our movement into action? Asana can begin to teach us. We develop such an intense sensitivity that each pore of the skin acts as an inner eye. We become sensitive to the interface between skin and flesh. In this way our awareness is diffused throughout the periphery of our body and is able to sense whether in a particular asana our body is in alignment. We can adjust and balance the body gently from within with the help of these eyes. This is different from seeing with our normal two eyes. Instead we are “sensing” the position of our body.

Boom! Such an epic book.

While practicing asana, we are practicing expanding the awareness beyond the intellect.

And that starts with focus!

By bringing the attention down into focal points around body we create relationship and understanding between mind and body, so that every movement becomes intelligent, and every cell of the body like an “eye of awareness”.

This is the “yolking” or “union” that many reference as the best translation of the word “yoga”. Literally — shortening the distance between body and mind so that we can begin to understand how to expand the awareness.

It’s like crawling before we learn to walk. Awareness expands to the edges of the physical body, then beyond.

Every time we engage with an asana there are many focal points to evaluate. The edge of the back foot in Warrior 2, the pinky toe, the knee over the front ankle, the gaze past the fingertips. At the start, there are only so many of these we can “think” about during the few breaths we stay there before moving on. Engage, let go, move on, engage again.

Over time the edges of those moments begin to soften and blend together. We can “be” right at the fingertip but also at the back heel at the same instant. Eventually, we can “be” everywhere in our body at once. Embodiment.

Suddenly focus doesn’t seem to be so correlated with productivity, does it?

With a yoga practice, focus is not a means to an end, but an end in itself.

It has inherent value and underpins all the “enlightened” states we might occasion in ourselves during the course of a lifetime.

From diligent focus, can come awareness.

From open awareness, can come presence.

In presence, all things can be seen as one.