Selfish vs. Selfless Thought

Sutra 5: Vṛttayaḥ Pañcatayyaḥ Kliṣṭākliṣṭāḥ - The Mental Modifications (Vrittis) Are Fivefold And Are Either Painful or Painless

So love, though it appears to be a painless thought, ultimately ends in pain if it is based on selfishness.

The fifth sutra is where Patanjali’s work starts to get into the details.

If you combine 1-4 you can read it like maybe the briefest accurate intro paragraph to yoga practice possible to write.

Now begins yoga.

Yoga is the restraint of the fluctuations of the mind-stuff.

Then the Seer abides in its true nature.

At other times, the self appears to identify with the fluctuations of the mind.

What we’re doing in a traditional yoga practice is learning to restrain the attention from being caught up in the fluctuations of the mind (thoughts, feelings, judgements).

When that occurs, the “Seer” (read: seat of attention, consciousness, that which perceives) bears witness to itself. Ask yourself: when the attention is not distracted and the mind is clear, what do you then become conscious of?

That is the same as ones true nature, according to Patanjali.

So whatever our consciousness is made of, it’s the same as what makes up everything.

If that sounds too obvious to be profound, sit down and try to pay attention to (a.k.a. — be conscious of) only your breath for 2 minutes. Then let me know if you can confidently say that you know what consciousness is like when it isn’t layered over with thought.

Unless you were raised in monasteries or have spent years in meditation or just live under a rock, chances are that you’ll fail to count to 10 breaths without seeing some form of thought rise in the background.

At other times, the self appears to identify with the fluctuations of the mind.

May I suggest an amendment for the modern era?

4 Most of the time, we are completely lost in thought and (mis)identify with the story we keep telling ourselves about our experience.*

But don’t be discouraged.

In the next sutras, Patanjali begins to typify thought, which is meant to help us begin to become at least more aware of the lenses that color our perception of the world.

Imagine finding out you’ve been wearing dark sunglasses all your life without knowing. If you can’t take them off, it’s at least useful to know what color tint the lenses have. If you know you tend to have green lenses, you’ll think twice when you see a stoplight.

However, before listing the five types of thought, Patanjali conveniently gives us a simple dichotomy to work with. He says:

The mental modifications (vrittis) are fivefold and are either painful or painless

Painful or painless — simple right?

The Swami’s commentary is useful here:

Instead of these terms “painful” and “painless” we might be able to understand this point better if we use two other words. Call them “selfish” thoughts and “selfless” thoughts. The selfish thoughts ultimately bring pain.

In my humble estimation, this is why most major religions and the more redemption-oriented philosophies emphasize a focus on selfless thoughts. It’s useful from a utilitarian perspective because, simply put, when you’re thinking first about others, and seeing to their needs before your own, you necessarily disengage with the idea that you are lacking or worse off.

Try feeling bad about yourself when you’re handing out food at the Salvation Army on Christmas…you might feel pain through sympathy, but you certainly aren’t going to as preoccupied with the state of your bank account, whether or not your team won last weekend, or whatever generally occupies your mind. Those are, statistically speaking, likely to be the main causes of your personal suffering. As we all know, even the richest among us can suffer deeply under the tyranny of a mind preoccupied with its own subjective problems.

Problem solved?

Thinking = suffering, but can’t stop thinking, so just think about others >> be better off.

In an ideal world, with everyone thinking about everyone else, how could needs go unmet? While you see to the needs of 10 others, surely someone out there would see to yours.

But we all know this isn’t how it’s playing out on this shakespearean stage.

Thoughts are like water in a water balloon. Press down on one spot, it rises up on all sides to surround it.

The trouble is that its super, super, super easy to end up with selfishness sneaking its way into what we think are selfless thoughts.

In social groups where these values of selflessness and charity are upheld, we tend to reinforce behaviors that display them with praise and other tangible or intangible rewards. The child who helps up a fallen comrade on the playground within the view of parents knows on some level that doing so improves their likelihood of being accepted and cared for within the social unit. What happens when we remove the “watchers” though? Go read Lord of the Flies if your school system didn’t already force you to in 6th grade.

Beyond in-group / out-group dynamics and survival instincts, there’s the commonly held notion that by being a good person in life (read: being unselfish, giving to the poor) you are rewarded in whatever form of afterlife to which your geographic & cultural heritage tends to subscribe. This is obviously problematic for anyone looking to act with complete selflessness uncomplicated by ulterior motives of any kind.

Even on a molecular level, the dopamine surge one might receive from handing a dollar to a pan handler is suspect for marring our true intentions, keeping us coming back to “do good” like some kind of altruistic drug dealer. Maybe that’s natures way of creating harmony amongst beings inevitably prone to conflict.

I’d like to suggest a simpler way to think about it.

Thought is thought.

Self is self.

Selfish thought is thought that the self participates in.

Selfless thought is thought that the self does not participate in.

When you first begin meditating in the Headspace App, the instructor teaches you to picture the thoughts like a train passing you by. The goal is to create a little separation for the practitioner so they can simply recognize “I am here. My thoughts are there. Therefore, I am not my thoughts.”

A fun practice that proceeds from that one is to try and trace each thought you become aware of back to its origin. “I noticed I was thinking about pumpkin pie…where did that come from? I was imagining Thanksgiving dinner last year…picturing how full I was…ah, right! My stomach rumbled and I realized I’m hungry.”

However the more we chase the thoughts, the more we tend to find that there is no clear beginning, nor reason for them. They are simply there. Whatever thought you are having now, try to trace it all the way back to it’s origin. You might find points where new trains begin (like the stomach rumbling), but the tracks actually continue way on back into the obscured and convoluted recesses of memory.

I’d be willing to posit that there isn’t a single thought in the history of humanity that, when traced fully back to whatever theoretical beginning it has, is completely free of at least some form of self regard.

So don’t bother.

A simpler aim to work on is differentiating between the thoughts that really take you for a ride, and those that pass on by like cars on the train.

This applies to thoughts you want to have and also those you don’t.

We’ve all probably had the experience of being criticized and having the person’s words rattle around in our heads for the rest of the day (maybe week). We’ve also all probably spent some time basking in the mental portraits of our idealized futures — those glory days after we’ve finished building passive wealth, having kids, being mad at our parents, and learning every fact on the internet. Then we can be happy and free.

But as the first sutra states: NOW begins yoga.

The moment to unite with, well, the moment — is always now. The time for presence is already here. The idealized future never comes. Even if you mark it on the calendar, when that day comes, you’ll still just be in another passing moment like this one.

So our practice is designed to provide us with many opportunities to recognize when the attention has become caught up in the fluctuations of the mind.

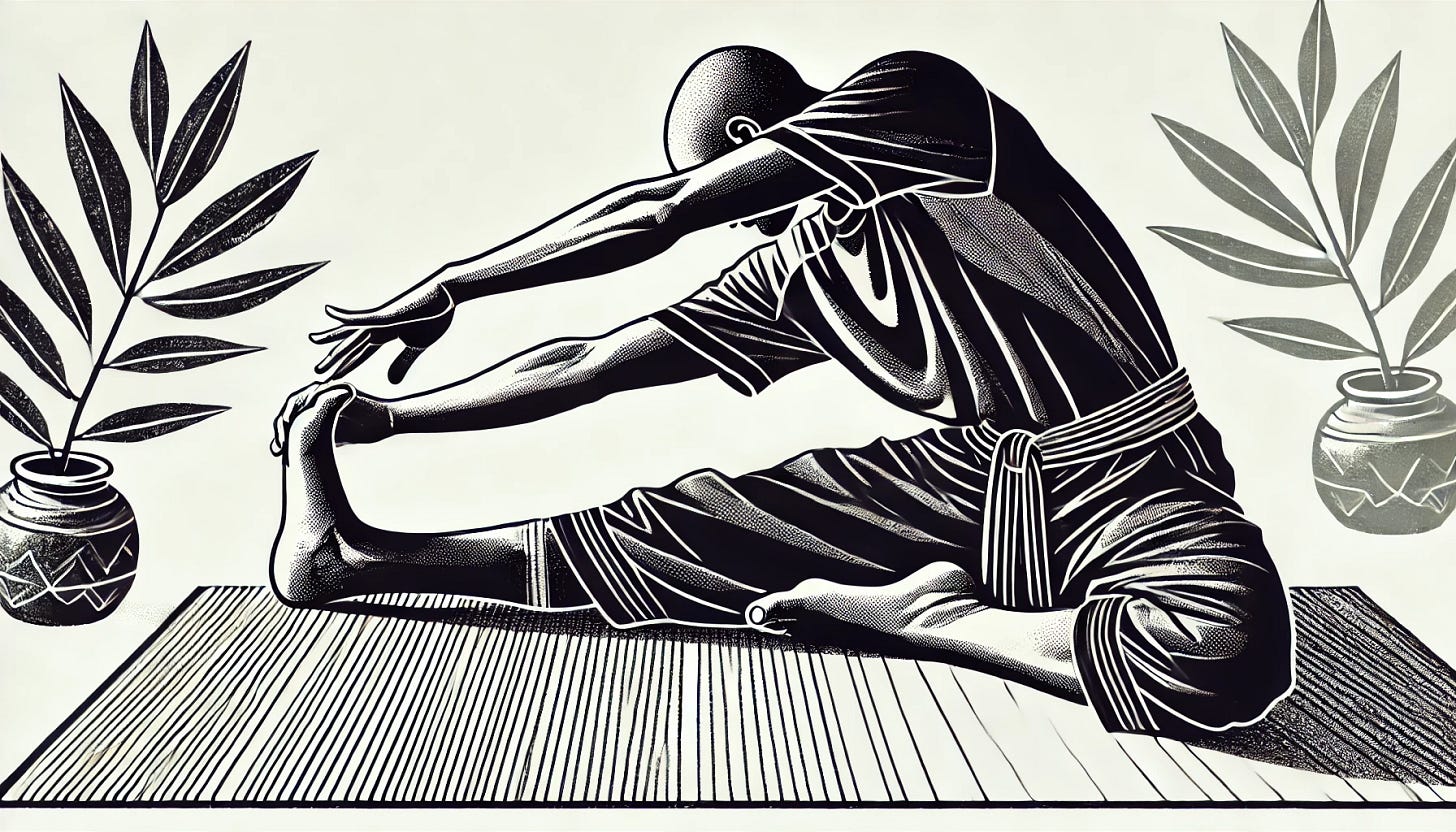

As you take an asana, the core aim is to keep the attention focused on the breath, and let the breath flow naturally. That’s really it.

Sometimes there are physical barriers that obstruct the breath (tightness, injury, having a normal skeletal structure and not being a freaking contortionist like the 100lb girl up in the front) — but remember to hunt for the non-physical barriers too (being pissed your muscles are so tight, being arrogant and doing postures that harm the body, or being preoccupied with what the ex-gymnast is doing that seems better than what you can do).

It is in witnessing those moments, when you recognize that you’ve become lost in thought again, that the opportunity to practice liberation arises.

That’s why we return to the same postures again and again.

Don’t worry about being able to touch your toes, as nice (and arguably healthy) as it is. That’s a by-product of the more important work.

Each time you revisit the work an asana entails, there’s a way to deepen into the things the posture illuminates. There’s always another layer to encounter, and perhaps begin peeling back.

There’s always going to be another thought arising.

Let it be.

Let it pass.

Sit back in the seat of awareness in your natural state of equanimity.