Supreme Non-Attachment

Sutra 16: Tat Paraṁ Puruṣa Khyāter Guṇavaitṛṣṇyam — When there is non-thirst for even the gunas due to the realization of the Purusha, that is supreme non-attachment.

Sutra 16

तत् परं पुरुषख्यातेर्गुणवैतृष्ण्यम् Tat Paraṁ Puruṣa Khyāter Guṇavaitṛṣṇyam When there is non-thirst for even the gunas due to the realization of the purusha, that is supreme non-attachment.

Ok, are you ready? This is where the sutras start to get esoteric.

These words like “gunas” and “purusha” are broad concepts with layered meaning depending on context. Yoga philosophy itself is a niche within the broader scope of Hinduism, and is not the only subset of thought to reference terms like “purusha”.

Before we go further, I want to pose a simple challenge to you as a reader/practitioner:

Leave it undefined.

It’s easy to Google the explanation of purusha and be like “oh, ok, I get it — grand cosmic consciousness…it means God”.

Try to approach these italicized words like literary mirages. When faced with something initially incomprehensible, the brain seeks to apply a form to it before it’s really sure what it is. And honestly that’s fine, so long as you’re willing to quickly let go of the synthetic applied comprehension.

Let me illustrate this point briefly…

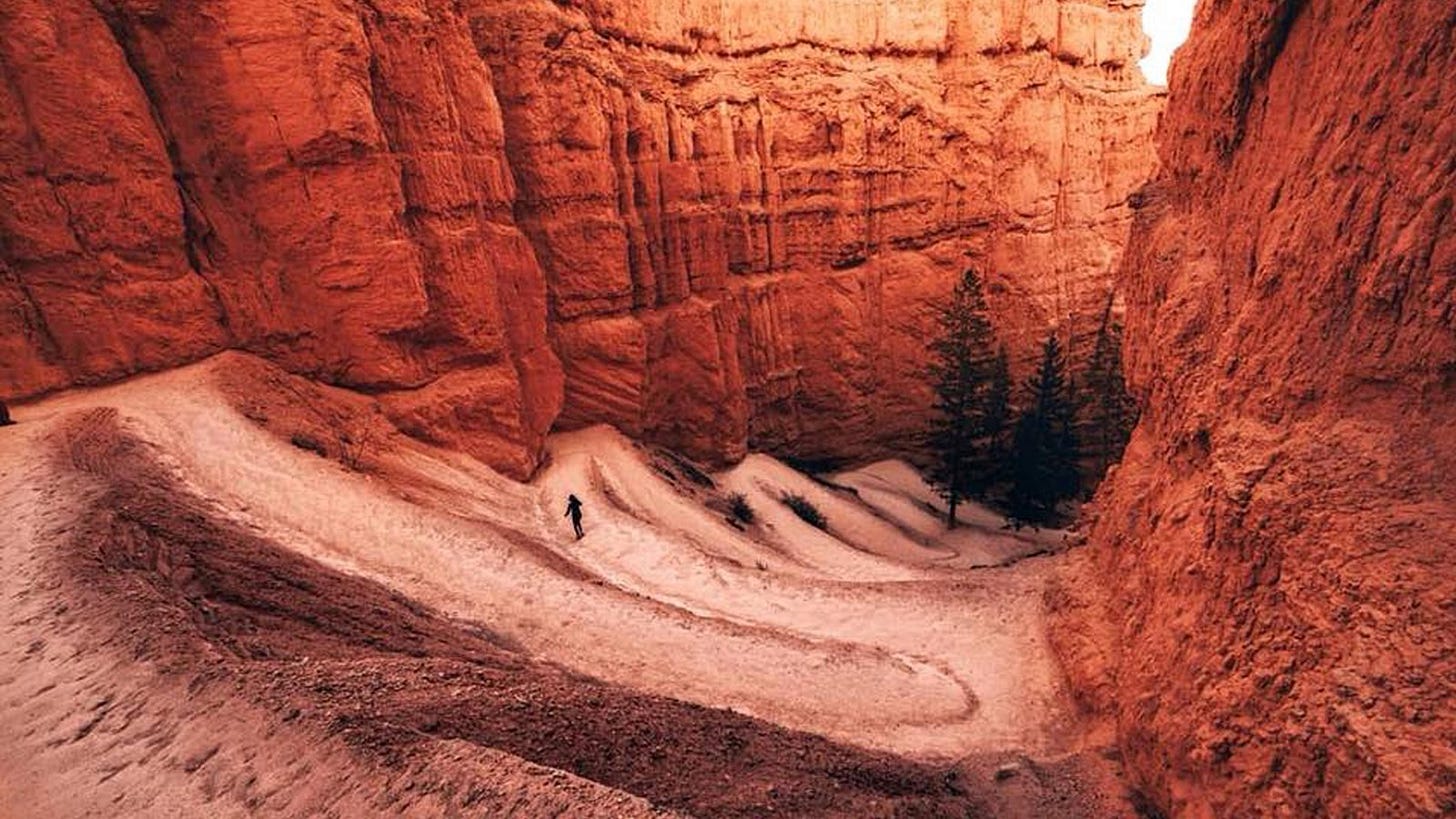

— you’re looking up at the top of a steep, sandy hill

— if you try to go straight towards it, you lose your footing and slide back down

— so you find a foothold and shuffle sideways along the face of the hill

— you turn back and head the other direction and keep looking for the least steep sections

— repeat the process to work your way up the otherwise unassailable hill

It’s a switchback trail. Make sense?

It’s perilous to go straight up, so you have to take an indirect approach. Another metaphor is looking straight into the sun. You never quite get to look right at it, but it’s in all things that you see, when you think about it.

The caveat is that you do, in fact, double back.

If you want to hold the concept of Purusha next to the idea of a Judeo-Christian almighty God, it’s not entirely wrong to do so, and it probably can help to understand the idea. But you’ll lose the nuance if you stop there. It’d be like continuing on a diagonal path past the switchback turn…if you do manage to reach the top of the cliff along that way, it’s not going to be at the same point.

In theory the view up there should be more or less the same regardless of where you ascended, but that’s another topic entirely.

For the sake of this discourse, let’s just aim to maintain a beginner’s mindset and approach each idea as a new thing.

So if you read the definition of purusha and are like “ok that sounds similar to what I think of when I think of God” — that’s totally fine, but try not to completely fill the space of inquiry with preconceptions. Leave it somewhat undefined.

In my opinion, the deepest beauty of yoga practice (and it’s deepest utility) is that it doesn’t rely on the acceptance of prescribed definitions for its parts.

It’s an experiential practice.

I could expound endlessly on this — but, said in the simplest way, the aim is not to comprehend purusha…it’s to experience it.

Where many philosophies and spiritual lineages say: “this is what XYZ is, here’s what you should do in light of that understanding”

Yoga says, simply: “here’s what you should do to see XYZ in your own conscious experience”

In other words, yoga says: find out for yourself.

It’s easy to forget that guiding principle (especially when we get into the nitty gritty here breaking down the texts associated with the practice), so I figured I’d put a callback here at this point.

With that said:

Sutra 16

तत् परं पुरुषख्यातेर्गुणवैतृष्ण्यम् Tat Paraṁ Puruṣa Khyāter Guṇavaitṛṣṇyam When there is non-thirst for even the gunas due to the realization of the purusha, that is supreme non-attachment.

Sutra 15 explains that an enlightened mind is one that does not get attached to the various thought forms that arise in consciousness. But there’s an even deeper level of non-attachment to consider:

Supreme Non-Attachment

Basically, there’s first the level where you’ve trained the mind to be disciplined.

— a sensation arises, and you feel the urge to follow the thought form it creates.

— you smell apple pie, and you think “I ought to go get a piece, I love apple pie!”

Practicing non-attachment means you have that thought, but you basically just think better of it.

— you smell apple pie, and you think “I ought to go get a piece! No, wait — I’ve already eaten plenty. I’m watching my blood sugar. I don’t really need pie.”

Whatever your reason, you basically decide not to follow that immediate urge.

Now, you guys probably know I’m generally suspicious of the idea of hierarchical thinking in a yoga context. I try not to use cues like “take the fullest expression of the pose” because it implies an additive attitude — as if the things you do combine to create a desired end state / goal.

For me, yoga is more so an reductive practice.

You’re looking to reduce the amount of things in your mind by focusing purely on the breath and movement. We do that in order to come closer to the raw momentary experience of the substrate of life (breaking the illusion of separateness from the world at large).

So rather than attempting to use the practice as a means for whatever ends you desire (doing headstands, feeling better) I try to think of it as the ends itself. The goal is already reached — you are intrinsically here, now. The means is learning to notice that more sustainably.

However, there is something fundamentally different between a body that can reside in Warrior 2 for two minutes without any visible signs of effort, and a body that begins to tremble after 10 seconds.

And as we know, that difference is the result of a function of time and repeated effort.

So it is with non-attachment vs. supreme non-attachment.

Returning to the apple pie metaphor —

A simply unattached mind has the thought: “I should have pie” but decides not to.

A supremely unattached mind doesn’t even have that first thought.

When there is non-thirst for even the gunas

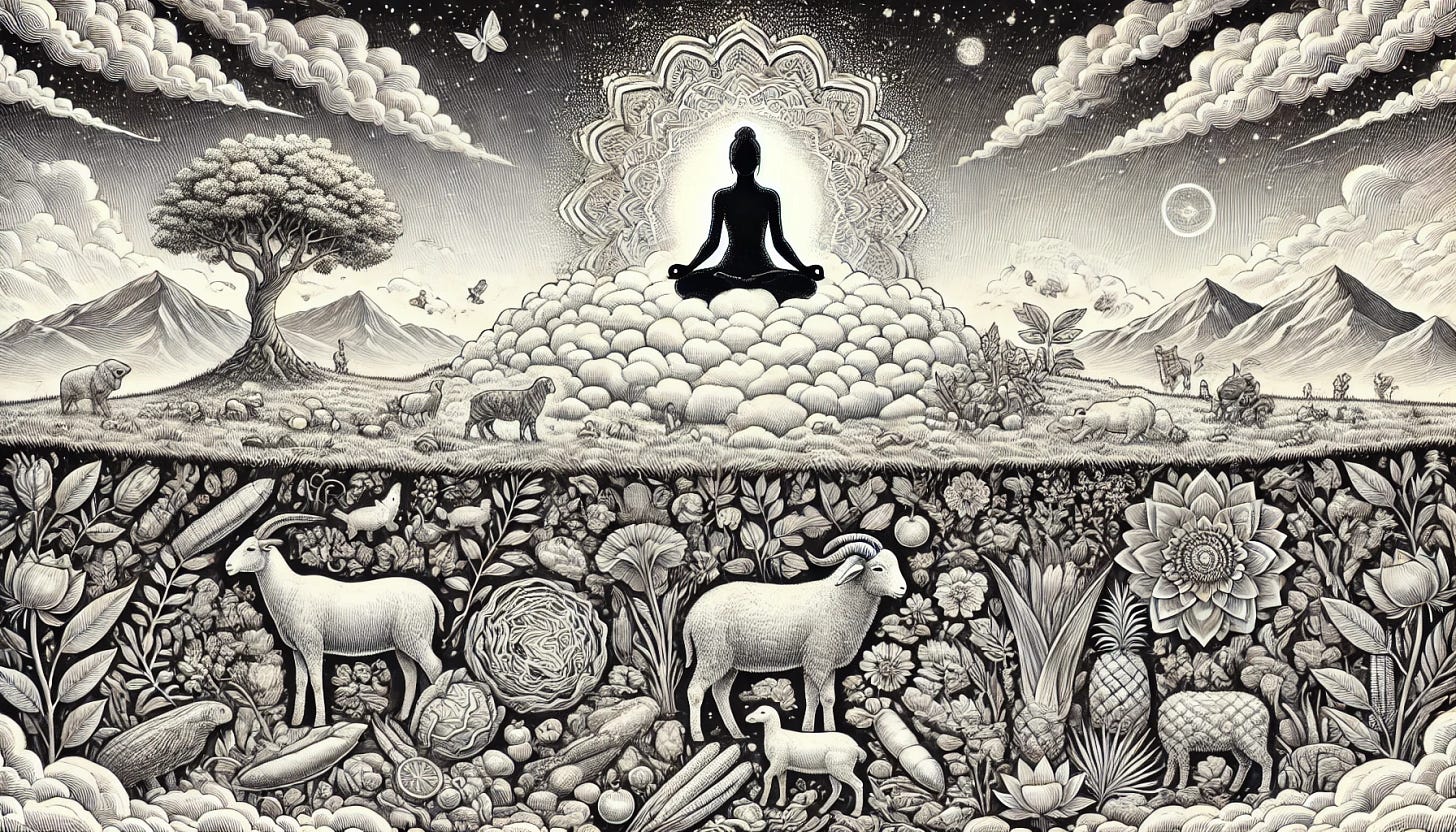

In a yoga context, gunas refer to the three fundamental qualities that make up all of (physical) nature.

They are thought of as the underlying energies that influence our physical, mental, and emotional states. These come from Sankhya philosophy, one of the six classical schools of Indian thought, and are foundational in yogic and Ayurvedic understanding.

The three gunas are:

Sattva – Purity, harmony, clarity, balance

A sattvic mind is calm, clear, and content.

Rajas – Activity, passion, restlessness

A rajasic mind is driven, distracted, or anxious.

Tamas – Inertia, darkness, ignorance

A tamasic mind is clouded, depressed, or resistant.

Yoga practice generally aims to cultivate sattva—not by denying action or rest, but by creating balance between these three forces. Over time, as the mind becomes more sattvic, it becomes a better tool for meditation, self-inquiry, and ultimately liberation (moksha).

So Patanjali is saying that a supremely unattached mind isn’t influenced by these underlying energies.

To a supremely unattached mind, the smell of apple pie may be experienced purely as an appearance in consciousness. It need not be considered pleasant (if you like apple pie) or foul (if for some psychotic reason, you don’t like apple pie) — it simply is. A mind that has transcended the push/pull of the underlying energies (gunas) isn’t beholden even to the arising urges that external stimuli cause.

The question is…

How the heck does a mind transcend being affected by physical nature?

Ok, I warned you it was going to get esoteric.

The way an individual answers this question can be, in many senses, a determinant factor for what religion they follow or what spiritual practices they spend time on during life.

When there is non-thirst for even the gunas due to the realization of the purusha, that is supreme non-attachment.

Patanjali states that this supreme non-attachment arises due to the realization of the purusha.

Simple enough, right? Just tell us what purusha is so we can “realize it” and transcend the bonds of physical reality + become enlightened.

Side note: in a way, it is really simple. And I think it’s the simplicity that results in this becoming such a complicated topic / branching off point for practitioners that are studying the deeper levels of yoga philosophy.

In yoga texts, you’ll often see the idea of small “self” (lowercase {s}) vs big “Self” (uppercase {s}). This is one of the simplest ways to describe the idea that the individual ego/consciousness/being (small self) is either an illusion or just a small part of a much larger entity.

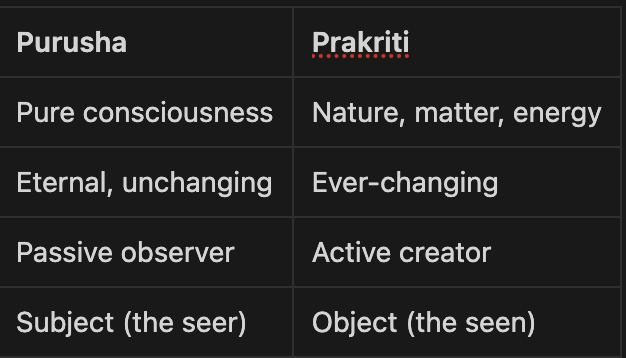

Additionally, Purusha is often cast against it’s supposed opposite — Prakriti. Here’s a table to break down the two concepts as they are typically presented in yoga texts.

So, where are we on this spectrum?

As a matter of experience, the answer depends on what aspects of your conscious experience with which you’re currently identifying.

Usually it’s somewhere in the middle.

Think: are you the sum total of your thoughts, feelings, emotional tendencies, and neurological patterns? Or are those just appearances in the space of your conscious awareness?

As far as I can tell, that’s basically the question the first yogis sought to answer. If we sit still long enough and the fluctuations of thought eventually subside (or become stable enough that they can be looked past) — what’s left?

It’s not all that complicated, really. It’s freaking hard to achieve (thoughts just keep coming no matter what you do! That’s why you basically have to ‘do nothing’ to watch them subside.), but as a matter of theory we can approach this easily…if the things that tend to fill the space of your awareness evaporate or become transparent enough that they no longer obstruct your field of ‘vision’, what will you then ‘see’?

According to Patanjali, once a yogi “sees” this (realizes purusha) the thirsting mind can be forever satiated.

Sri Swami Satchidanada describes the notion like this:

The moment you understand yourself as the true Self, you find such peace and bliss that the impressions of the petty enjoyments you experienced before become as ordinary specks of light in front of brilliant sun. You lose all interest in them permanently. That is the highest non-attachement.

Be careful, though. For us westerners, this attitude can easily lead to seeking shortcuts.

Though Satchidanada and Patanjali seem to imply that all you need is a glimpse to be stable forever, I doubt they think of attaining that glimpse as anything other than the result of long and sustained practice. In fact, that’s Sutra 14 😉

Practice becomes firmly grounded when well attended to for a long time, without break, and in all earnestness.

One of the most elemental aspects to yoga practice is learning to break your engagement with the externalized thoughts that we tend to define ourselves by.

Simply, the mind might believe that the body is capable of more than it is.

We test those assumptions when moving through a flow to find out where the underlying reality truly is. And the way we do that is, in effect, by sitting back in the seat of awareness that underlies all of our conscious experience.

Maybe you’ve been a fit person all your life, and one day you bend your knee into warrior 2 and a painful sensation arises. You have a choice to make. This information runs contrary to the story that’s been built up in your mind that you are a fit person and you don’t experience the same discomfort as the saps in the back row struggling to hold poses.

— you can ignore it, demanding that your body take a shape that your mind believes it to be well suited for.

— you can fear it, backing away and never attempting to bend your leg again to avoid the discomfort it might cause.

— or you can observe it, back away for a moment, and attempt to find a way towards the posture that doesn’t cause pain.

Do you see how this practice encourages us to sit back in that primary seat of awareness over and over?

Whether or not experiencing yourself as that awareness constitutes experiencing purusha, or whether there even is a difference between purusha/prakriti (non-dualistic vs. dualistic schools of thought) is something that’s likely better evaluated after having visited that state of being.

So, like everything in this practice ought to be — find out for yourself.

Stay with the breath and let it guide you back to the present moment again and again. Whatever arises there will be a much better teacher than any person ever could be.

Perhaps you will notice that the things which used to drive you subside with time, and it becomes easier to stay steady in the face of challenging moments.